Let’s take two quotes, mash their ideas together, and see what we get:

“Perpetual devotion to what a man calls his business, is only to be sustained by perpetual neglect of many other things.” — Robert Louis Stevenson

“If I were to let my life be taken over by what is urgent, I might very well never get around to what is essential.” — Henri Nouwen

I’ve been working from home and working for myself for over 4 years. One of the most empowering lessons I have learned over these past 4 years has been regarding my own limitations. Not merely my limitations of time, but also of energy.

In any given day I usually have 3 hours of good writing time in me. A couple hours of reading. Hopefully an hour or two of researching, thinking, or decision making. And maybe an hour of admin and other busywork.

If I push my day to include more than that, the returns on that extra energy is very little. Though the workaholic in me wants to squeeze in a few more tasks, there is a point when the responsible and productive thing for me to do is leave my office and stop working altogether.

Honestly, at times it can be difficult to let myself quit while I’m ahead for the day and go upstairs to be with my family, or go run errands, or just lie down and stare at the ceiling while I listen to what is going on in my imagination.

Albert Einstein once said: “Although I have a regular work schedule, I take time to go for long walks on the beach so that I can listen to what is going on inside my head. If my work isn’t going well, I lie down in the middle of a workday and gaze at the ceiling while I listen and visualize what goes on in my imagination.”

Over my years of working from home, I feel that too much focus on the “act of productivity” is to miss the forest for the trees.

Being “efficient” is not what’s ultimately important. I want to do my best creative work and I want to have thriving relationships. Meaningful productivity means showing up to do the important work on a regular basis.

Time management, task management, focus, diligence — these can help keep me on track, but they are not the end goal in and of themselves. I want to focus first on the important work itself.

Have I written today? Have I daydreamed? Have I been contemplative? Have I had an inspiring and encouraging conversation? Have I helped somebody? These activities are far more important than the checkmarks I make on my to-do list.

When you work for yourself, there is an oceanic undercurrent that pulls you into the details of your job. The thousand responsibilities of administration and communication and infrastructure. These are important, to be sure, because without them your business would cease to be. But (at least in my case) these are the support structures at best. The foundation of my business is not the ancillary administration; it is the muse.

“You can do anything, but not everything.” — David Allen

I am in the fortunate position that I don’t have to deal with email to do my job. In fact, the inverse that is closer to the truth: the less time I spend doing email the better I can do my job.

There are a few types of emails that I always pay attention to, and a handful of people whom I try to always correspond with in a timely manner. But I have rules and flags set up for those so that they are always sure to get my attention in my inbox.

For the rest of my emails, chances are I won’t ever reply to them. The reason I’m such a poor email correspondent to most people is that I just choose not to spend much time in email. Instead, I choose to spend my time doing other things such as writing, reading, managing the the administrative and financial logistics that accompany working for yourself, and spending as much time with my family as possible.

I could easily spend 3-4 hours every day reading to and replying to the messages in my inbox. But it’s not just the time and correspondence aspects of email that I chose to say no to — I’m also preemptively avoiding the decision-making and judgment-making requests that incoming emails ask of me.

Many of the emails I get are requests for my time, in one way or another. Either a request for an interview, an app review, to be a beta tester, etc. I would love to give my time and attention to these things if I could — I know I’m missing some great opportunities and relationships. But that’s just the way I’m letting it be — it’s an unfortunate consequence of my choice to be “poor” at email.

But if I were focus on all the incoming emails, and pursue all the opportunities that those messages presented, then I’d have no time, energy, or focus left for what is my most important work.

My friend Chris Bowler wrote about this. Saying: “Can we all agree to just let go? To stop caring that we might miss something big, something important? Reality is, we are all missing something important in front of us every day, while we carefully scan our feeds, missing the suffering, the joy, the simple state of being all around us. Our families and friends, our neighbours, our complete strangers.”

If I said yes to all the requests and opportunities and potential new relationships coming to my inbox then I’d have another full-time job, and I wouldn’t be able to write anymore.

My approach to email is not unlike the approach with one of the co-founders of Google has. David Shin, a former Google employee, shared this story:

When I worked at Google in 2006/2007, Larry and Sergey held a Q&A session, and this exact question was asked of them. One of them answered (I don’t remember which) with the following humorous response (paraphrased):*

”When I open up my email, I start at the top and work my way down, and go as far as I feel like. Anything I don’t get to will never be read. Some people end up amazed that they get an email response from a founder of Google in just 5 minutes. Others simply get what they expected (no reply).”*

I spend about 20-30 minutes a day in my email, and whatever I get to I get to. And whatever I don’t, unfortunately, goes unanswered. Because for me, Inbox Zero is actually all about the outbox. Inbox Zero means I choose to focus my time, energy, and attention on creating something worthwhile instead of feeding some unhealthy addiction to constantly check my inboxes. It means I care more about this moment than I do about my narcissistic tendencies of knowing who’s talking to me on Twitter. It means I care more about doing my best creative work than about keeping up with the real-time web and being instantly accessible via email.

By “pre-deciding” that the majority of requests for my time and attention over email just go unanswered, it gives me a fighting chance at doing my best creative work every day. Not only does it give me more time to focus on that which is important, but it gives me more creative energy to do my best work during that time.

In The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, there’s this great line: “Order and simplification are the first steps toward the mastery of a subject…”

Mann’s line carries the same truth as the earlier quote by Robert Louis Stevenson. Our devotion to a subject can only be sustained by the neglect of many others. Our devotion to that which is important can only be sustained by the neglect of that which is non-essential.

Your story doesn’t have to be about email. I bet you a cup of coffee there is something you can decide to be poor at so you can be better at something else.

Finding something we want to do is the easy part. Now we must decide what we will neglect, and then we have to grow comfortable with being in that state of “perpetual neglect”. Something not easily done in a culture that tells us we can and should have it all and do it all.

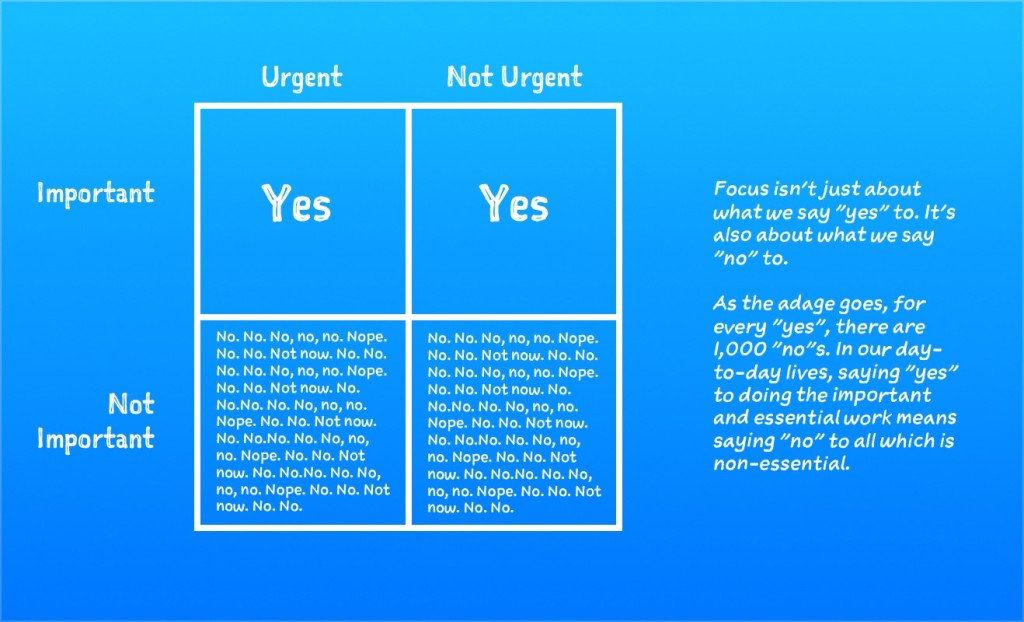

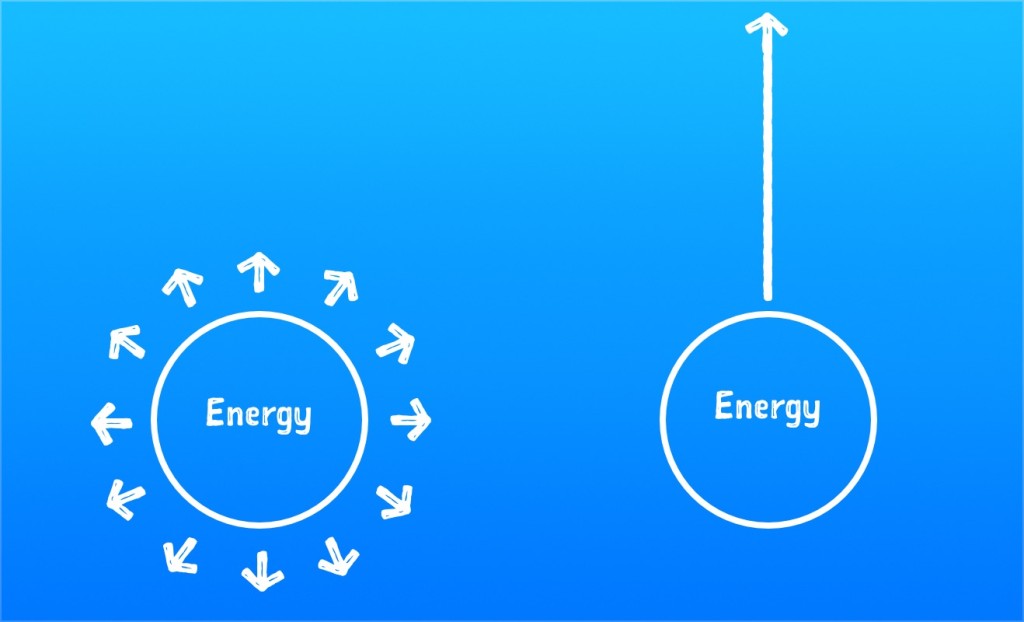

But what happens when we try to do it all? In his book, Essentialism, Greg McKeown has an excellent diagram comparing the difference between our efforts when we have many pursuits versus focusing in on just one thing.

When we are spending a little bit of time on a million different projects, areas of responsibilities, tasks, and activities, then we make very little progress on any of them. And our efforts are stretched thin. However, if we focus our energy on only the most important things — that which is essential — then we make meaningful progress. Not to mention, it just feels more rewarding to focus on one important thing and do it with excellence.

When we take a moment to consider what our most important work is, we tend to think mostly about what we want to accomplish and do and be.

But why not also think about what we will not do? What tasks and pursuits will we give up or entrust to others? What areas of our time, energy, and attention will we simplify in order to create the space and the margin to do what we want?

We can do anything we want, but we can’t do everything. Which means that for every “yes” there are 1,000 “no”s.

P.S. I built a guided, online course that can help you be more focused with how you spend your time and energy. If you liked this article, I bet you’d love the course.