Neven Mrgan is a designer, developer, and writer. He works at Panic, Inc., writes a popular weblog (or two), draws video game graphics in his spare time, and his last name is a bit of a mystery.

In this interview Neven and I discuss graphic design, life at Panic, and other miscellany.

The Interview

- Shawn Blanc: Until you joined Panic in 2008 you mostly did freelance work building web apps, correct?

- Neven Mrgan: I did freelance design and development work — mostly on the web — for a few years, and I had more or less interesting day jobs that time as well. I worked as an engineer on very straight-laced business web apps until 2007. This wasn’t terribly fun, and to be honest, I wasn’t too good at it either. Early in 2007 I decided to start sticking to graphic design and UI design, since I was never going to be a kung-fu-grade developer.

- Shawn: Your job with Panic seems like a perfect match in the sense that you fit right in as another clever, funny, nerd. But on the flip side, now you work in a team setting with a company that builds desktop software as opposed working solo on web projects. What led you to take the job with Panic?

- Neven: Regarding desktop software, it was somewhat new to me indeed. Sorry to bring up iPhone this early in the conversation, but it was a big catalyst for me in several ways; it was the first time I was doing non-web UI design. That was the roundabout route I took to designing desktop software.

As for Panic, the fit was just ridiculously good. They build excellent software, and they do so in a genuinely friendly, likable way. That combination is very uncommon. I was a recently married and ready-to-settle-down old fogie of near 30, and was big on leading a comfortable, quality lifestyle, and working on solid, long-term projects. Panic has those same goals.

Working on a team was a change after a year of clicking around in our home office. It’s hard to complain about the freedom of that arrangement, but I’ll do my best: a chair in your own house can be a pretty inert environment. It’s a bit of a bummer on a purely social level, and it can make your creative muscle slack as well. That’s been my experience, anyway. I’m happy to be surrounded by really smart folk as I click around now.

- Shawn: Do you ever miss working from home?

- Neven: I have that option currently and I don’t believe I’ve taken advantage of it more than three times (and even then, only because I had to be home for some reason). I can’t emphasize enough how much I like the vibe at my office. It reminds me of how I’d go to my high school’s super-awesome computer lab on the weekend, in the evening, and whenever else I could. I love what I do, projects and people and desk and all — it’s my job and my hobby.

- Shawn: You’ve got a lot of projects running — your couple cool weblogs, The Incident, your full-time job at Panic, and more. What does a day in your life look like?

- Neven: I half-wake up around 7:30 and remain in a hazy, floating, brain-puree state for about half an hour. This is when I get all of my stupidest ideas (like you know how some restaurants menus have a little V next to vegetarian items and maybe a clipart chili for “spicy”; what if they put an F next to “foodie” items? “Can the salad be made foodie?” -“Certainly; we can make it with Pouligny-Saint-Pierre and shave a black truffle onto it.”). Stupid ideas are excellent springboards, boosters for your thought and your daily mood.

I then check my email and RSS in bed; if it takes longer than five minutes, I save it for after I’m dressed. To do that I pick a Panic t-shirt from the stack I was given when I started (“your employee uniform”) and put my socks on in front of the computer. I briefly chat with whoever is online – usually only Matt Comi, my partner on The Incident. I take the bus to work; twenty minutes of book-reading on the ride, ten minutes of iPod while I walk.

I work ten to six. The morning is usually time for catch-up, unfinished business from the previous day, or quick production of ideas pickled overnight. Lunch is important because it brings the office together. It’s our most regular team meeting. The afternoon means serious work — Photoshop and Coda — and a snack break around four. I drink Coke Zero and endorse Nuvrei pastries.

Most days, I try to cook at least one meal; if there’s time to make dinner after work, I’ll give it a shot. If not, Portland has an embarrassment of excellent restaurants. Either way, I eat early and spend the evening working on whatever side projects I have going on. I go to sleep disgustingly late —midnight or 1 am.

This isn’t a schedule I make it a point to stick to. It’s just how things typically play out.

- Shawn: What are your favorite pieces of software?

- Neven: Photoshop, Coda, and Birdhouse.

I know, I know — give me a chance to explain.

I complain about Photoshop. Lord, do I. But it’s not only the essential tool for what I do, it’s a great tool also. I’ve done my best to give the competition a shot, and the truth is just that they don’t allow me to make the things I want to make (yet). Photoshop is internally and externally inconsistent, it’s bloated, it’s slow, and it crashes. But I use it more than I use my pants, and for that I love it.

Coda is an app I work on, so feel free to consider this a shameless advertisement. You’ll have to take my word for it: I used it before I started at Panic, and if I found a better app for web development, I’d promptly switch to it. Life is too short and the web too demanding to be a slave to cheap loyalty. It’s a great app.

Birdhouse is the only not-preinstalled app on my iPhone about which I have zero complaints. I use it regularly, and I don’t remember it crashing, slowing down, or confusing me once. You could argue that it does a tiny thing, but it does it well.

Sometimes I think that if this whole computer thing turns sour — if Apple becomes monstrously evil, if the Internet collapses, if I get old and stop grokking new technologies — I’ll switch to farming or cooking or poster design and be just as happy. Maybe that’s true. Some not-so-small part of me would, however, miss the wizardry I discovered some time in 1985 or so as I typed BASIC into my C-64: I can make a screen do things, and do things that do other things, and do different things depending on the things I do back to it. It’s a wonderful game.

- Shawn: Other than for your lack of development skills, why did you begin doing work as a designer and developer?

- Neven: Two beliefs: 1) Things should look good, and 2) Computers are cool. For the rest of my life I’ll be coming up with complicated explanations which boil down to those motivating principles.

So, I’ve really always wanted to be doing this or something like this. This or drawing comics, which I quickly learned was kind of not so hot.

- Shawn: Was it a lack of drawing skills that led you to computer-based design? (And do you have any old comic book drawings you’re willing to share?)

- Neven: I’m very happy with my drawing skills!

I decided to stick with computers because they could do things the real world couldn’t. I’m all in favor of creative restrictions — yay Twitter — but pen and ink’s lack of an Undo function doesn’t challenge me to do better work. It just makes me frustrated.

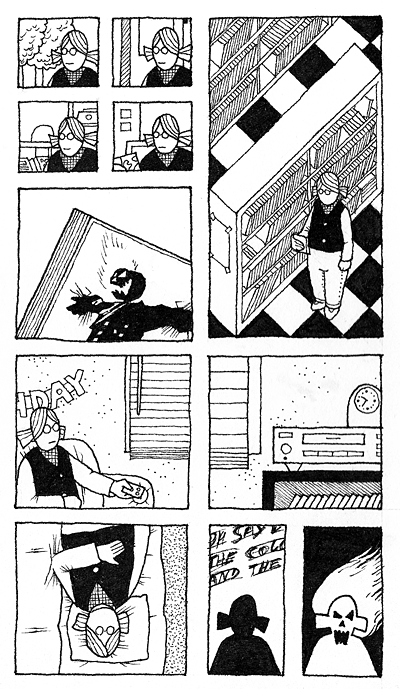

Now here’s a really out-of-context panel done some time in… 1998 or so, maybe?

- Shawn: If I ever want a future in art and design it will have to be with a computer. I can never get pen and ink to translate into what I want.

You’re not alone in with the belief that things should look good and computers are cool. But everyone has their own definition of what looks good and what the best tools for the job are. How do you define when a design looks good? Has that definition changed since seriously began sticking to graphic design and UI design?

- Neven: One thing I’m learning quickly is to evaluate designs and design ideas in terms of interaction: how they behave under what circumstances, how they work with other elements. That’s sort of new to me, though designing for the web has always been about flexible, unpredictable layouts and such.

A thing looks good to me when I fall in love with it; that’s test #1. Test #2 is, ok, that’s sweet – what is it? Does it say something, mean something, is it an “it” or an “It”? Test #3 is the more ponderous goatee-rubbing over how the design scales and translates, whether it’s too trendy or too dated, etc.

Sometimes I learn to eventually accept designs as excellent solutions even if they didn’t hit me right away. And sometimes designs I greet with a WOW bore me very quickly. But it’s very rare that I will love and cherish a design if it has to be “explained”.

It’s not important that I love everything I design. But hopefully it happens pretty often.

- Shawn: How would you recommend someone with no facial hair go about completing test #3 as a part of their own design critiques?

- Neven: There are a number of question you can ask about a design once it’s grabbed you.

- Will it scale, not just physically, but across cultures, age groups, platforms, ideas? Will your icon idea make sense to a busy person working in a dark room?

- Can any part of your design be abstracted and used elsewhere? Would anyone want to steal it? (You better wish they would!)

- If you’re breaking an established pattern or convention, are you doing so with good reason? With what are you replacing what you’re destroying?

- What if the things you, yourself, like to use were designed in this way? Remember Kant’s categorical imperative, “Act only on that maxim which you at the same time wish to be a universal law.”

You will add more questions to your list over time; you will also drop some as times change and as you develop your own priorities (the point is not to be able to answer “yes” to every question on the list).

Now here’s the important thing: DO NOT write down the list. Don’t put checkboxes next to questions and save it all as a file. Don’t print it out. Don’t ask people you work with to start using it. This way lies madness; or at least boredom, burn-out, and blandness.

My feeling is that many creative endeavors are like this; you should learn specific techniques and aesthetic guidelines, but ultimately you will want to simply do a lot of work and let the aesthetic judgment become a second nature. A good musician can, for the most part, “let their fingers play” instead of focusing on translating each sound-idea into a specific finger movement. A good baker will measure things, but they will only make consistently awesome bread when the dough “feels” right under their fingers. There’s no magic, destiny, or talent at work here, just a gradual process of practicing until the back of your head can do most of the work, not the front.

So, long answer short, learn as much as you can about the principles of design, about its history, and about other people’s work. But try to let it all soak into your brain through constant creative and functional use, not through cramming or some sort of workflow standardization.

- Shawn: How much, then, do you suppose good design sense boils down to talent versus practice?

Can tools and rules, in and of themselves, produce a quality designed product?

- Neven: I just realized I’ve been harping on the 90%-perspiration thing without going into why the remaining 10% — “the squishy bit” — is important. It’s frustrating to even think about it because it leads me to a mildly fatalistic state where I just throw my hands up and decide that if good design is a matter of talent and destiny, then it isn’t worth doing since most people won’t even know it when they see it. Which is true, in many ways. Why does a designer spend any time deciding between Helvetica and Univers? Most people won’t know or care either way. Or maybe they will, on some unreachable level — maybe Helvetica will appear more generic (at least today it will), Univers more technical; the former, more “design-y”, the latter, more “informative”.

A designer will obviously have far more opinions of this sort about the minutiae of design. Now, partially these will be a product of the designer’s education and work experience. Maybe they once read Univers was a good choice for signage, or a teacher told them it was a modern classic. Maybe they’re sick of Helvetica.

But given enough time, these opinions will become more than restatements of other people’s attitudes. Different aesthetic prejudices — sometimes clashing ones — will come together in one head to create a unique taste and signature.

A great trick I learned from the science writer Matt Ridley: in debates over nature vs. nurture, remember that one is a function of the other, so it doesn’t make sense to say talent “contributes 30%” or some such thing. They’re linked in a much more complicated way.

To answer the second question a little more directly: no [tools and rules, in and of themselves, cannot produce a quality designed product].

- Shawn: You’re right that most people won’t know good design when they see it. But in the context of UI design, that’s the point.

Jeffrey Zeldman wrote a great definition of Web design in an article, “Understanding Web Design“. He said:

“Great web designs are like great typefaces: some, like Rosewood, impose a personality on whatever content is applied to them. Others, like Helvetica, fade into the background (or try to), magically supporting whatever tone the content provides.”

Like you said, Neven, the vast majority of people won’t even notice your design. But the very act of them not noticing is (usually) the proof of a good design. On the flip side, of course, are times when the people should notice the design. It’s the Form Versus Function debate that UI designers are faced with every day. The mark of a great designer is one who knows when to chose which side of the issue and how find the balance between both sides.

The reputation for Panic when they come to a form-versus-function hurdle is to find a simply stellar solution (like Cabel’s 3-Pixel Conundrum). Has Panic developed any official guidelines for working on UI design? Have they ever conflicted with your personal preference?

- Neven: I work under surprisingly few constraints as far as what must or mustn’t be done. We’re pretty aggressive about staying ahead of the curve, so we insist on certain not-yet-widespread widespread technologies (resolution-independent graphics, for one). We love a good visual metaphor — Coda’s taped pages in the Sites view — but it has to make sense, and it can’t be realistic at the expense of usability, or to the point of sickening cuteness.

If we’re adding a feature, we almost never go “ah, there’s already a standard control for that, we’re set.” We might just end up using the existing design, but not before we poke it within an inch of its life. Why does this menu look like this? What if we had never seen it before — how would we build it?

As Cabel has mentioned, we’re big on weenies: elements that make a design stand out immediately. There’s nothing wrong with a simple metal window, but there’s nothing great about it either, and more things should be great!

This is the designer’s nastiest temptation — over-designed, needlessly custom chrome which neither fits nor improves the platform. This is the land of Windows Media Player skins. Often we try to “fit the OS better than it fits itself”, if that makes sense; if we think an Apple widget betrays the hand of an intern, we’ll draw our own, better one. This is the thing people notice the least, but it’s a great personal victory.

To get back to rules and guidelines, nothing is off the table, really. I realize that when I say that I’m excluding things obviously off the table: round windows, animated toolbars, blue chrome, scripty type. Part of this intangible, complex, wavelength-syncing soup we as a team live in is the baseline of quality and aesthetic we all appear to share: let’s not do Thing X, ever.

As for my personal preferences, I’m probably more conservative than the team as a whole. I’m seeing that (slight) difference as a learning opportunity, so I’m happy to report there have been no freak-out arguments over shades of green. You’ll just have to take my word for it, our tastes are creepily aligned — if we weren’t such motormouths, we’d get along fine with an occasional nod or frown.

- Shawn: Has the process of completing a design project changed for since joining Panic? Is there a boss or an Art Director who signs off on your work?

- Neven: “Sign-off” is, like most things with us, a matter of conversation and feeling out people’s reactions more than a structured process. I’m the sort of person who has to get total agreement from others before I’m fully happy, so I usually gauge everyone’s feedback as I work, and this hopefully results in a universally accepted design by the time I’m done.

- Shawn: I have done freelance work from my home as well as being a designer working with a team in an office environment. When I freelanced I had a handful of creative friends whom I could send drafts of my work to and ask for their feedback. Ultimately if my client liked it and I liked it, then it was a done deal.

In the team dynamic, I enjoy having the ability to tap a friendly co-worker or two on the shoulder to get instant feedback and dialog about the project I’m working on. But there can, at times, be a downside to that setting insofar that more people need to sign off on the finished piece — it’s not just me and the client anymore.

I prefer the team setting significantly more because it helps me stay more productive, more creative, and more dynamic in approaching problems. But (and maybe it’s just me. But) it can be frustrating when there is not universal head-nodding approval for every project I’m working on or leading.

- Neven: I find that a team of our size — about a dozen — is a really good middle ground between the isolation of working alone and the tar-pit indecisiveness and slowness of focus groups, market research, surveys, and gigantic corporate meeting fests. I am constantly getting new ideas from the team (while bouncing them off everyone). At the same time, I don’t have to sit and wait for a design to make the rounds and get approved by a chain of people.

Other than company size, a few other things about Panic help make this possible. We’re close in age, interests, and general attitude about life and work. Everyone is great at their job, and this makes it very different from working for clients. The client’s preference and criticism may or may not come from actual knowledge of the product, the audience, and the technology we’re talking about.

Here at Panic, I know I’m getting feedback from a tech-savvy person smarter than me who is also a regular user of the product. If they have a complaint — and I should also mention they’re good at knowing what matters how much when it comes to design — it means there’s likely a real problem I should solve. Maybe there’s something I forgot; maybe the design should be a little more polished. Or maybe my idea was crap to begin with. I am far less likely to defend the design by simply saying “I think it’s good”. Keep in mind that this often happens when working for outside clients, and it’s not good for the designer. Not letting yourself get challenged will keep you from exploring new ideas. The trick is to be challenged by knowledgeable people you like and respect.

I don’t know of any online resource for those, though, so… Your parents/karate instructors were right: there are no shortcuts, it’s going to take time!

The End…

Thank you, Neven.

For more interviews with extraordinary designers, developers, writers, and web nerds, visit here.